Beyond the emergency kit: Disaster preparedness for families – certificates, community, and more

Continuing from the previous article, explore unique challenges for families with children in case of natural disaster and learn about preparedness for that.

Protecting your little ones: Expert advice on disaster preparedness for families – 2/2

Japan is prone to natural disasters like earthquakes, making disaster preparedness essential. While many households already stockpile water and food, families with children face unique challenges during evacuations. These challenges are highlighted by Mami Tomikawa of the Tokyo-based NPO MAMA-PLUG in her recently published book, ‘The Latest Version: Disaster Preparedness Book for Families with Children: A Comprehensive Guide––Made with 1648 Affected Moms and Dads*’. MAMA-PLUG has extensive experience supporting families displaced by earthquakes, from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake to the 2024 Noto Earthquake.

This article, following on from our previous piece on daily preparedness for families, explores further steps families can take, including essential information on obtaining vital documents like disaster certificates and damage certificates.

*The original title: 冨川万美 (2024) '全災害対応!最新子連れ防災BOOK--被災ママパパ1648人と作りました'. Tokyo: Shodensha (祥伝社).

Summary

Earthquake, rainfall and wind hazards: A reality of living in Japan

Adapting mindsets: A call for change in Japan

Don't hesitate to take action!

Overwhelmed by disaster fears? Finding ways to cope

Earthquake, rainfall and wind hazards: A reality of living in Japan

Yumiko: As you mentioned earlier, gradually adjusting your lifestyle to accommodate this will help you identify the specific actions you need to take. I had thought my lifestyle was fairly disaster-prepared, especially since I've lived in Japan for a while. However, based on what I've heard today, I now realise there's always room for improvement. Considering that foreigners may have varying levels of disaster preparedness knowledge, unlike Japanese people who have undergone extensive disaster prevention education, what do you think are the absolute essentials they should know?

Mami Tomikawa: I've spoken with many people from overseas, and I've noticed significant differences in how people perceive earthquakes, even within couples. For example, a woman from a country with no earthquake experience attended our course after speaking with her Japanese mama-tomo (mother friends). They made her realise she needed to learn more about disaster preparedness. However, when she told her husband what she learned, he dismissed her concerns, saying, ‘If there's an earthquake, we can always go back to your country.’ He reassured her there was nothing to worry about, leaving her unsure how to explain the importance of disaster preparedness.

Y: Once a major earthquake hits, it's best to assume that air travel, including airports, will be disrupted. But what advice do you have for couples who might have differing opinions on how to respond, like the one you mentioned?

MT: It's true that people's reactions to earthquakes can vary greatly, even within families. This is especially true for couples where one person comes from a country with little earthquake experience, unlike, say, New Zealand. People have different cultural backgrounds and beliefs, which influence how they perceive risk. This can make it difficult to agree on a course of action. However, it's crucial to understand that Japan's geographical location makes it prone to various natural disasters.

Earthquakes, typhoons, and flooding are frequent occurrences in Japan. Typhoons and flooding are annual events, so preparation is key. A good first step is to review the hazard map for your area.

Most local governments provide these; you can contact your local government office to obtain one. It's important to visualise what might happen during a typhoon, flood, or even a major earthquake, and plan accordingly.

Adapting mindsets: A call for change in Japan

MT: Building a network with your Japanese neighbours is also important.

Y: Some people already have a network through their school-age children, but for those who don't, connecting with the Japanese community can be challenging. Many foreigners feel they have limited opportunities to do so. We know this is important for disaster preparedness, but it can be difficult.

MT: It's also crucial for us Japanese to shift our mindset. During disasters, it's especially important to remember the diversity of our communities. We have foreigners, elderly residents, and people with disabilities – all with varying needs.

We Japanese should make a conscious effort to connect with a wide range of people regularly and foster a more inclusive environment.

Through our activities, we emphasise the importance of changing our own attitudes first. We need to be mindful that we have foreigners in our communities, some of whom may not be fluent in Japanese.

Furthermore, in a large-scale disaster, it's crucial to avoid being alone and to stick together in groups. This applies to everyone, including men, who sometimes tend to act independently. We need to identify those in our community who might be isolated and proactively include them in groups.

Expect the unexpected: Disasters can transform Japan's normally safe streets into unpredictable environments

Y: So, in a large-scale disaster, do you mean it's not just women but men who should avoid being alone?

MT: Exactly. For safety reasons, everyone should stay in groups, regardless of gender. Unfortunately, disasters often lead to an increased risk of burglary, robbery, and even sexual assault.

Y: That's right. In recent years, there have been reports of sexual assault against women and children in evacuation centres. These are horrific, unforgivable crimes that often go unreported.

While many people consider Japan a safe country, it's important to be aware of these risks. In other countries, looting can be common during disasters or large-scale disturbances. Japan might seem more orderly in comparison, but it's not immune to lawlessness.

MT: True. Things can descend into chaos very quickly. Disasters often lead to increased stress and, unfortunately, a surge in violence and crime.

It's been reported that crime rates can triple during such times. Women and children, especially, should take extra precautions. Never go to the bathroom alone in an evacuation centre; always have someone accompany you. Evacuation centre toilets are often located in less visible areas, making them particularly risky.

Understanding the differences between Disaster Damage and Victim Certificates: Don't get lost in translation!

Y: Besides personal preparedness, what other preparations should we make regularly? For example, how about understanding the role of our local government?

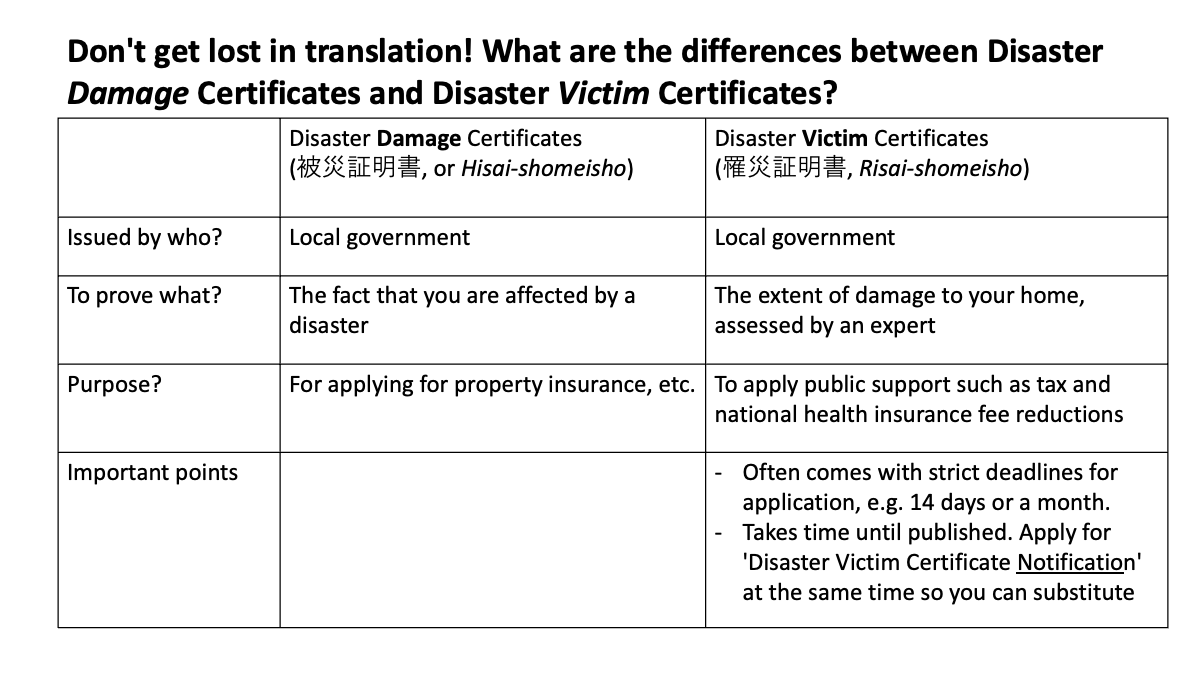

MT: That's a crucial point. Local governments have specific procedures after a disaster, such as issuing Disaster Damage Certificate (被災証明書, or Hisai shomeisho). Many people are unaware of these procedures, which can impact the financial assistance they receive. Unfortunately, most local governments don't provide information in multiple languages. It's essential to understand the necessary procedures beforehand. Accessing and understanding this information can be vital in securing support.

Y: Navigating the required paperwork after a disaster can be quite complex. Could you please tell us about the necessary paperwork and procedures, such as obtaining certificates, following a disaster?

MT: There are two types of documents issued in the event of a disaster: a Disaster Damage Certificate (被災証明書, or Hisai-shomeisho) and a Disaster Victim Certificate (罹災証明書, or Risai-shomeisho)*. Both of these are issued by the local government where you live. A Disaster Damage Certificate proves that you were affected by a disaster. It is a document that is required for things like applying for property insurance.

On the other hand, a Disaster Victim Certificate (hereafter a ‘Victim Certificate) is a document that certifies the extent of damage to your home. When you apply for one, an expert will investigate the current situation. If you have a Victim Certificate, you can receive public support such as tax and national health insurance fee reductions, as well as disaster victim living support funds. In addition, you will be eligible for support such as interest-free or low-interest loans from private financial institutions.

*Editorial Note: While Risai-shomeisho is translated as a Disaster Victim Certificate by the Government, the translation of Hisai-shomeisho varies. Please note that the English translations provided may not perfectly capture the nuances of the original Japanese terms. The diagram below is provided for clarification.

It's important to be aware of two key differences between the Victim Certificate and the Disaster Damage Certificate. Firstly, obtaining a Victim Certificate can take time. It's advisable to request a 'Disaster Victim Certificate Notification' at the same time you apply. This notification serves as proof that you've initiated the application process.

Secondly, there are often strict deadlines for applying for a Victim Certificate. In many cases, the deadline is quite short, such as 14 days or one month after the disaster. Sometimes, the deadline might even pass before the situation is stabilised. This can significantly impact your ability to receive financial assistance, so it's crucial to be aware of these deadlines and apply promptly.

Don't hesitate to take action!

Y: To stay informed about local disaster preparedness, why not contact your neighbourhood association and ask them about it?

MT: That's an excellent idea. Depending on your local government, they may hold evacuation drills in the area. You could take that opportunity to speak to the neighbourhood association president. City hall or ward office staff members are often present at these drills, so you could raise any concerns with them directly. This will help the neighbourhood association and local government understand the needs of residents, including foreigners, which is very important. It's also a good idea to get involved in disaster prevention activities within the school PTA.

Y: Many foreigners still feel isolated from Japanese society, regardless of their Japanese language skills. Do you have any advice based on your experience?

MT: It's often easier to start a conversation by talking about your children. You can begin by mentioning something about your kids and then move on to other topics. For example, you could say, 'I'm heard about this at school...'

Also, since Japanese people tend to be influenced by trends, you could try starting a conversation about something you saw on TV. For example, ‘I saw a programme about disaster preparedness on TV, what are you doing about it?’ This might be easier than suddenly bringing up the topic of disasters.

Y: What options are available for the foreign community to organise disaster prevention activities? Could MAMA-PLUG help with this?

MT: Certainly! We hold hundreds of workshops every year. We tailor our seminars to the group size, participant characteristics, ages, and so on. We begin with a consultation to determine what the participants want to learn and then design a programme accordingly. We offer introductory courses and can also accommodate participants with children.

Overwhelmed by disaster fears? Finding ways to cope

Y: Some people find it stressful to think about future disasters. They become so anxious that they want to avoid the topic altogether. It's a natural human reaction, but what can we do about it?

MT: The mental aspect is very important. It's true that thinking about disasters can be anxiety-inducing, so it's important to find ways to cope with that. How about exploring ways to refresh and relax yourself?

For example, if you have a child who can't sleep without a particular blanket or a bedtime story, make sure you can maintain that routine even during a disaster. The same applies to adults. Even if you don't usually think about it, you probably have habits that help you relax in your daily life. It's a good idea to identify those and perhaps even write them down.

You might realise that you drink coffee because it refreshes you, or that checking your favourite social media accounts each day is essential for you to feel connected. Perhaps you enjoy a piece of chocolate. When you reflect on these things, you can see what you habitually do to keep your spirits up.

Knowing yourself is also very useful in times of disaster. It's a simple concept, but it's an effective way to prepare. For example, if you realise that you need chocolate to relax, you might want to include some in your emergency kit, as it might be unavailable after a disaster.

Y: Are there any other simple things we can do to prepare?

MT: It's a good idea to download a household medical dictionary app or have first aid information readily available. During a large-scale disaster, medical institutions will prioritise treating those injured or rescued.

For example, in a large-scale disaster, emergency services may be overwhelmed, even for situations that normally require immediate medical attention, such as a child having a seizure or accidentally swallowing something. Be prepared to take action without panicking in such a situation. The Tokyo Fire Department app provides helpful first-aid information and is available in English, Chinese, and Korean.

*Editorial note: Many English readers may already be familiar with the MSD or Merck Manual. The MSD/Merck Manual Home Edition app is available in English and Japanese, as well as Arabic, Chinese, French and Spanish.